Bethany Dearlove computational biologist

New paper: Rapid host switching in Campylobacter

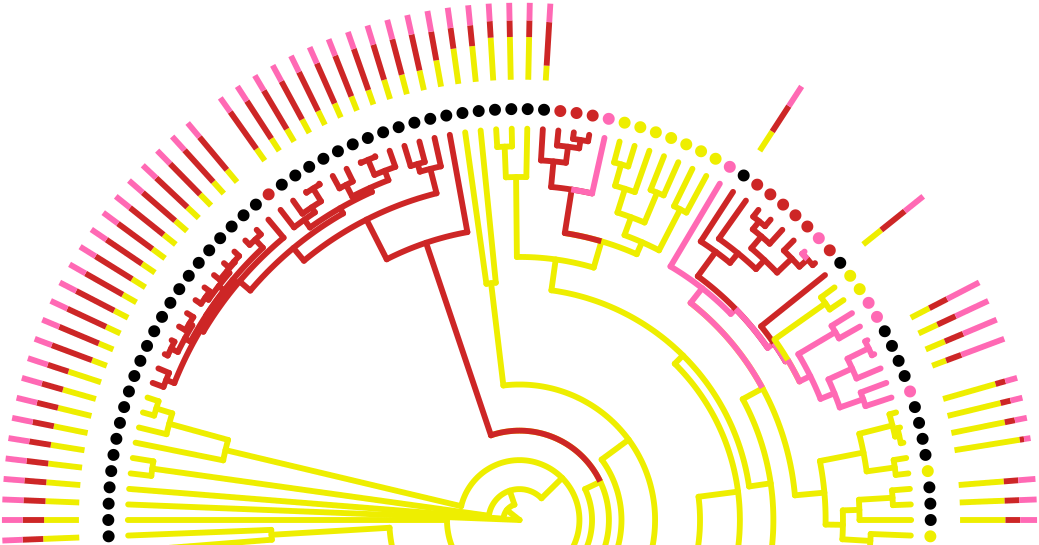

My new paper with Daniel Wilson, Sam Sheppard and colleagues on rapid host switching in generalist Campylobacter strains has been published in The ISME Journal (open access).

Campylobacter is the most commonly identified cause of bacterial gastroenteritis worldwide - with more cases than Salmonella, E. coli, Clostridium and Listeria combined. Infection is generally associated with food poisoning, particularly the consumption of raw poultry products. However, the Campylobacter genus comprises several widely distributed species of zoonotic pathogens, carried, often asymptomatically, in the gut microbiota of a range of mammalian and avian species, including, notably, those found on farms. As a consequence, opportunities for contamination of products including meat, poultry and unpasteurised milk can take place at any time from farmyard to fork. Although some strains of Campylobacter are only found in a single species, others appear associated with numerous host species. Indeed, some of the most common lineages associated with human disease are found frequently in both chicken and cattle, making it hard to infer the true source of infection.

Previous work has focused on MLST typing, using only 7 genes representing about 1% of the full genome. The idea behind this new paper was that the increased resolution afforded by whole genome sequencing could reveal previously undetected differences between the strains found on chicken, versus those, say, on pork or beef. However, somewhat surprisingly, this was not found to be the case. Instead, we show that common strains of C. jejuni and C. coli infectious to humans seem to be rapidly switching between different hosts species - much more quickly than mutations can accumulate to differentiate sub-populations between those hosts. This suggests these lineages are adapted to a generalist lifestyle, permitting rapid transmission between different hosts.

This conclusion also highlights that whole genome sequencing by itself cannot substitute for intensive sampling of suspected transmission reservoirs when searching for the source of human infection.

September 3rd , 2015 by Bethany Dearlove